It is late, nearing midnight. A toenail moon emerges from the clouds, glances through my window at the scraps of paper, mugs of old coffee, and blinking fairy lights. I am tired, but not sleepy, caught up in a voyage through old photographs tucked away in a folder labelled “misc” on an old harddrive.

On one screen: me, 20 years ago. Friends. Old apartments. Raves. On the other screen, I’m flicking through Nikita Diakur’s website, a dialogue forming. There is something weirdly familiar in Nikita Diakur’s art. These simplified, malformed puppet people in this broken urban space strike a resonance within me.

I grew up in rural Ireland, against a backdrop of vast grey skies, a rolling ocean, and countless wet sheep. I moved to the city when I was 17 to go to art college, diving into the chaos and the uncertainty, the grey skies replaced by grey concrete, the rolling ocean by rolling cigarettes, and the countless wet sheep by countless sweaty nights out dancing.

In Diakur’s Fest figures gather to dance and eat and speak and mess-about. Figures whose large forms are carefully dressed in tracksuits and colourful dresses, large smiles and wide eyes that look out into the world. (Apologies for the low-res images, to see Diakur’s work in all its glory, check out his website.)

There is a wildness inherent in each scene - the people and objects are pulled forward by an immense internal force that cannot be held back. Created using dynamic computer simulation, the works employ a physics that is, shall we say, janky as hell. Surprise or chance is a huge element in the work, with nothing ever seeming to behave or respond how you would expect it to. The AI has its own input, which Diakur does not try to control too much. Even though we can see the construction - the grid that holds the buildings, the strings that move the figures - there is little sense of order and control. Instead, there is the sense that anything could happen at any time. That there is a world of endless possibility and limitless potential within everyone…and sometimes it is the potential to destroy which has more power.

Dancing bodies disintegrate into spasmodic flurries of line and movement. Figures are sent swinging through the air, a path of destruction in their wake. Cars stand on end and human forms are stretched beyond their limits. The works are manic and silly and intense and funny and beautiful and ugly.

I continue to wade through folders upon folders of old photos. I see a pile of smiling people, fully clothed in a bathtub, their eyes bright red in the camera flash. I see four friends sitting up on a roof, silhouetted in the rising sun. I see a broken sunflower, grown proudly from a seed before being accidently sat on. I try to remember what it all felt like.

In Diakur’s work there is a gentleness to the treatment of the figures. They are each unique, deliberately dressed from head to toe. They are often bathed in a warm and beautiful setting sun. This dying light lends a sense of finality that asks us to look back on our time here through glasses tinted by nostalgia.

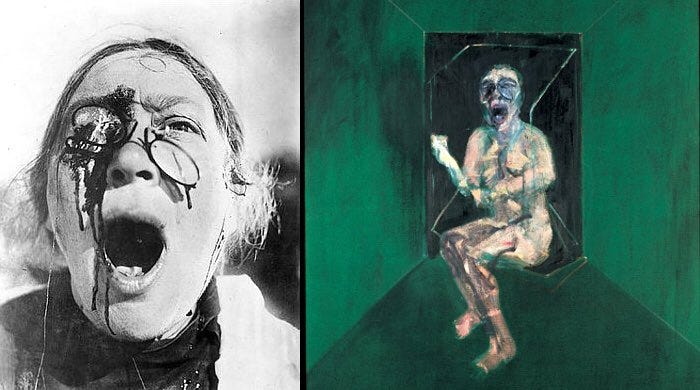

My tired mind picks up a thread of connection between Diakur and Francis Bacon. Lines which intersect the figures, suggesting construction, containment. Figures that disintegrate, that scramble. In Diakur’s work there is less of the weighty fleshiness of the human body, but there is still a powerful life force. In Stairs, Odessa there is a reference to Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, from which Bacon also drew inspiration.

Bacon’s work is dark, heavy, oftentimes oppressive. Diakur’s work is decidedly more joyful, more hopeful. It is perhaps a kind of optimistic nihilism. Everything is inherently chaotic and somewhat meaningless, but we can bring order to life through our attention. Our gaze and focus creates meaning from the madness.

If we care, things matter.

I send a few of my old photos to friends via text, the implied message being a cliched “where has all the time gone?”…I drag myself to bed and dream a restless dream of tumbling through the void, a ray of light at my shoulder.